• The Florida Torreya and the Atlanta Botanical Garden, by David Ruland, in Conifer Quarterly, pp. 10-14 (2007). Note: As of 2019, David Ruland is Greenhouse Manager for Atlanta Botanical Garden.

... According to fossil records, the Florida torreya is estimated to be over 165 million years old. Like many other conifers with such an impressive age, it was once scattered throughout the northern hemisphere. Scientists theorize the species was driven south by glaciers that once covered the northern latitudes. When the glaciers retreated, the Florida torreya was left isolated in small microhabitats of the southeastern United States, where it thrived for thousands of years.

... Many of the original Arnold Arboretum cuttings have matured into cone and seed producing trees [at Atlanta Botanical Garden] that, in total, form over 500 viable seeds per year on average. These plants are grown in the ABG "seed orchard" and propagules produced from these seeds have been used to facilitate the next phase in the recovery of this species.

... In 2002 ABG initiated a collaborative project with Florida State Park Service that involved reintroduction of seedlings into ravines at Torreya State Park (TSP), where Torreya taxifolia has been extirpated.... Great efforts are made to ensure that introduced plants are not planted in ravines where existing plants occur. The plants are bare-rooted prior to placing in the native soil. Four treatments are used on the outplanting: fungicide, fertilizer only, fertilizer and lime, and control. These experimental transplants will help determine the optimal treatment, if any, that is needed for future success reintroducing this species. A total of 200 seedlings have been outplanted in TSP and the survival rates so far are encouraging.

... Despite the successes of the conservation program, the Florida torreya faces a long road ahead to recovery. Even if wild populations were capable of producing viable seed, the Florida torreya would seem incapable of expanding its limited range due to a lack of a natural dispersal agent. The aforementioned squirrel has proven to be capable of seed dispersal but almost certainly is not the original prime disperser. It was most likely a large extinct animal, although speculation on such matters in the plant world is endless.

... The concern over the Florida torreya's inability to reclaim its former habitats has given rise to a movement among conservationists called "assisted migration." The basic idea is to see populations of T. taxifolia moved further north into more hospitable climates. It would be encouraged to integrate naturally, thereby securing the tree in the wild again. Torreya taxifolia does thrive in areas such as Asheville, North Carolina and even much further north. Indeed, as is the case with many types of plants, the cool night / warm day temperature differential would seem to be conducive to a healthier tree. The Atlanta Botanical Garden is not a proponent of such measures. It is prudent to establish safe-guarded populations in cooler climates within the confines of cultivated or human disturbed areas, not in pristine natural habitats. Therefore these plants can be further evaluated in a botanical garden setting and seed development encouraged without creating further ecological disturbance.

The Florida torreya is a glacial relic, seemingly stranded in an increasingly hostile niche without any natural means of escape or survival. This tree would certainly be doomed without the intercession of concerned individuals and institutions....

• October 2019 / Connie Barlow / VIDEO by Tallahassee Public TV station on Hurricane Michael Damage

Six-minute video titled Torreya State Park After Hurricane Michael: One Year Later was produced by WFSU, the public TV station affiliated with Florida State University in Tallahassee. The video begins with a look at the two unlikely survivors of the hurricane where the entrance road ends in a parking lot. Both Gregory House and a planted little grove of torreya trees at the lawn edge survived, the tall trees fallen all around them.

For viewers and readers familiar with the paleoecological foundation undergirding the drive for "assisted migration" poleward of the glacial relict Torreya tree, the video offers a few hints of the steephead ravine ecosystem similarities in the park to habitats now found in the southern Appalachians. The actions of Torreya Guardians are of course not mentioned. But the accompanying essay does say this:

|

|

"In the 1950s, a fungal blight wiped out a population of about 600,000 Torreya taxifolia in the region. The Florida Park Service, Nature Conservancy, and the Atlanta Botanical Garden have been working to revive the Florida torreya, a species whose future may lie in its likely ancestral home of North Carolina, where planted trees have thrived disease free."

|

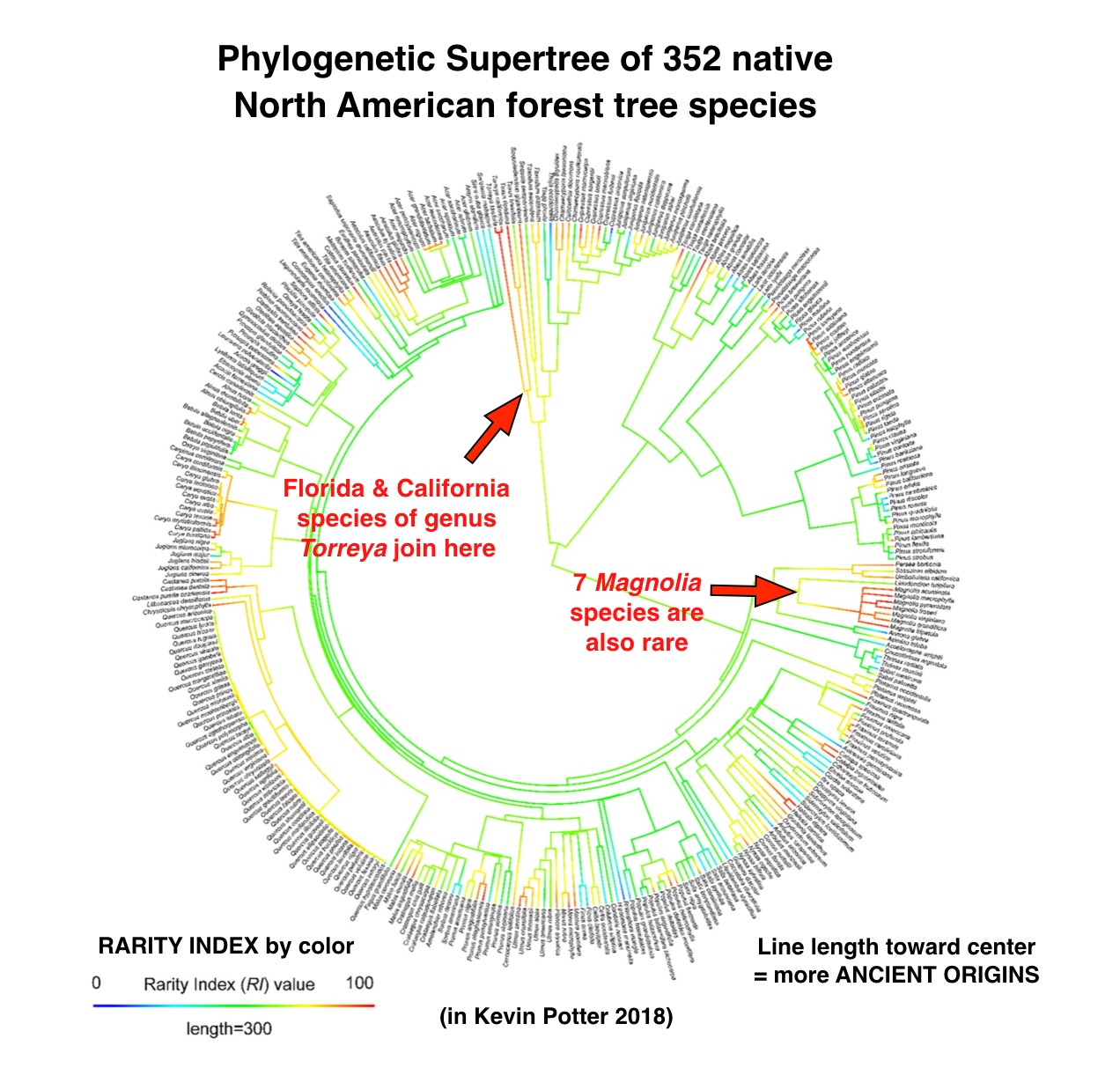

• August 2019 / Connie Barlow / 2018 paper ranks genus Torreya as both very rare and ancient

| |

Kevin M. Potter, Dept. Forestry and Environmental Resources of North Carolina State University, published a paper in the May 2018 online issue of the journal Biological Conservation:

"Do United States protected areas effectively conserve forest tree rarity and evolutionary distinctiveness?"

Connie Barlow added red type and arrows to the original figure, left.

Notice that the sister species in Florida and California of genus Torreya are among the rarest of 352 tree species native to North America.

These two Torreya species also are among the most ancient tree lineages.

Together, rarity and age of origin call out for the highest levels of conservation attention.

|

• May 2019 / Connie Barlow / New paper useful for understanding male/female flexibility in Torreya

During our site visit to the mature Florida Torreya trees in Louisiana, our guides recounted their experience with the largest specimen beginning as male and then starting to produce some female buds on various branches — culminating in seeds that fell and germinated beneath the parent tree. A 2019 paper on Striped Maple of eastern North America (a subcanopy species, just as is Torreya) can help us understand how to observe and possibly predict an individual's ability and propensity to begin producing seeds. Access full text.

EXCERPTS: "... Male-dominated sex ratios occurred consistently across study sites and the 4 years that sex expression was monitored. Approximately one-third of trees [studied as single branches cut and grown in a lab conditions] changed during any 2-year period. The five most common transitions were, in descending order of frequency: from non-reproductive to male, male to full or partial female flowering, female to dead, and from partial to full female flowering...."

|

|

"... We have shown that in the sexually plastic tree Acer pensylvanicum a variety of factors influence expressed sex. Chief among them are previous sex and the health of an individual. Although the general theory regarding ESD in dioecious plants has indicated that females are often found in relatively better condition and at larger sizes, we find the opposite pattern in this species.... We show that mortality is disproportionately high in females...."

|

The Strange Mix of Vegetation Along the Apalachicola River

• Chasing Ghosts: The steep ravines along Florida's Apalachicola River hide the last survivors of a dying species, Torreya taxifolia, by Rob Nicholson, 1990, Natural History Magazine

EXCERPTS: ... All the unknowns confound any recovery plan. Is Torreya an early victim of global warming and a precursor of a new wave of inexplicable extinctions? Has local land use destroyed this Torreya habitat? Is there any point in trying to fortify existing populations by replanting if a virulent pathogen lurks unchecked? Will propagations of cuttings from existing wild trees carry a new pathogen wherever the new trees are distributed? Or, frozen by doubt, will plant scientists do nothing while the unique species slips away, tree by tree?

... The Apalachicola Bluffs and the ravines that dissect them are at the cusp of the deciduous woodlands and the lush subtropical jungle. It is an undecided forest, its luxuriant ecotone having been shaped by the forces of glaciation during the Pleistocene era. As a New Englander used to deciduous woods, I was unsettled by seeing beech, maple, and hickory mixed with bold fan-leafed palmettos, spiky yuccas, and huge evergreen magnolias.

... In June 1989 I joined Mark Schwartz and we surveyed as many ravine systems as possible, carefully mapping and labeling the plants growing there.... When we returned in the fall, we collected small cuttings, tissue samples, and soil samples for genetic, propagation, and pathological studies. Alarmingly, in just a few months, a number of our mapped trees had been lost — to deer rubbing, disease, and even falling limbs from the upper canopy. The species was going extinct before our eyes and will probably not last another generation.

... To travel the bluff tops down the steep slopes to the creek beds, 100 to 200 feet below, is to read a primer in zonal plant ecology. Species are stratified by drought tolerance and light demands. Those on the tops of the bluffs are adapted to full sun and dray conditions. Endangered gopher tortoiss burrow amid opuntia cactus, longleaf pine, yuccas, and bushes of sparkleberry. At the base of the ravines can be found the rare Florida azalea, native bamboo, and Sabal palmetto amid a thick tangle of Florida star anise that rivals the tangled rhododendron 'hells' of Virginia and Tennessee.

The steep pitch between these two zones includes a number of endemic plants: croomia, Ashe's magnolia, florida yew, pyramid magnolia, and Torreya, as well as species known throughout the eastern seaboard, such as American holly, American beech, tulip tree, and leatherleaf. The southern magnolia, known to me as an ornamental tree of glossy green, rubbertree-like leaves, festooned with outlandishly large white flowers, here grew as 100-foot forest giants, with a a first branch higher than a man could throw a rope and with crowns so dense they blotted out the sun.

The Florida yew, like the Torreya, belongs to the Taxaceae family. It is also a rare endemic, whose range is actually smaller than, and within, that of Torreya. Although occupying much the same habitat, the yew has not been affected by whatever is affecting its larger relative. The ravines are not identical, however. Variations in grade, soils, aspect, and moisture create subtly different habitats, some of which Torreya can tolerate. It dominates nowhere, and past references indicate it never did. It is an occasional midcanopy, midslope tree found on sandy limestone sols. In general Torreya prefers good drainage to flat, constantly wet soil; and while it is almost always found in filtered, dense shade, I have seen cultivated Torreya grow perfectly well in full sun. In its native environment, the stinking cedar may be better able to compete on the shaded slopes than in sunnier areas.

... More than 2,500 cuttings were collected from 166 trees and were treated with a variety of hormones to promote rooting. These were brought to Harvard's Arnold Arboretum, where 2,100 were successfully rooted and potted. The accession number of the sampled trees follows each of these clones (and any subsequent propagations) with the particulars as to the plant's original location in the wild. Therefore, in the distant future, ravines might be replanted with the same genetic material that once grew there. Cuttings taken from the wild five years ago are growing well and so far show no signs of disease.

... While the few remaining saplings may outlast the blight, not many people who have seen the trees would wager their homes on it. More likely, clusters of trees, propagated from specific ravines, will be grown in botanical gardens, universities, preserves, and state parks. This Florida native, as evidenced by the few healthy trees in cultivation, seems to thrive on the southern slopes of the Appalachian Mountains and is more cold tolerant than its present range would suggest. Possibly an Apalchicola refugium can be re-created, an artificial Torreya forest where pollen can float, genes mingle, and the evolution of the past hundred million years can continue, even if it is in a pitifully discounted format.

ABOVE LEFT: hickory trunk in front of evergreen magnolia canopy, with trunk of American Beech at center.

ABOVE RIGHT: Several shrubby palm species beneath a large beech in Florida's Torreya State Park, along the Apalachicola River. The botanical mix in the "steephead ravines" in this park is a treasure because the same site served, just 18,000 years ago, as a crucial "pocket reserve" in which the botanical richness of today's southern and central Appalachians took refuge at the peak of the last glacial advance. (Photos by Connie Barlow.)

|  |

|

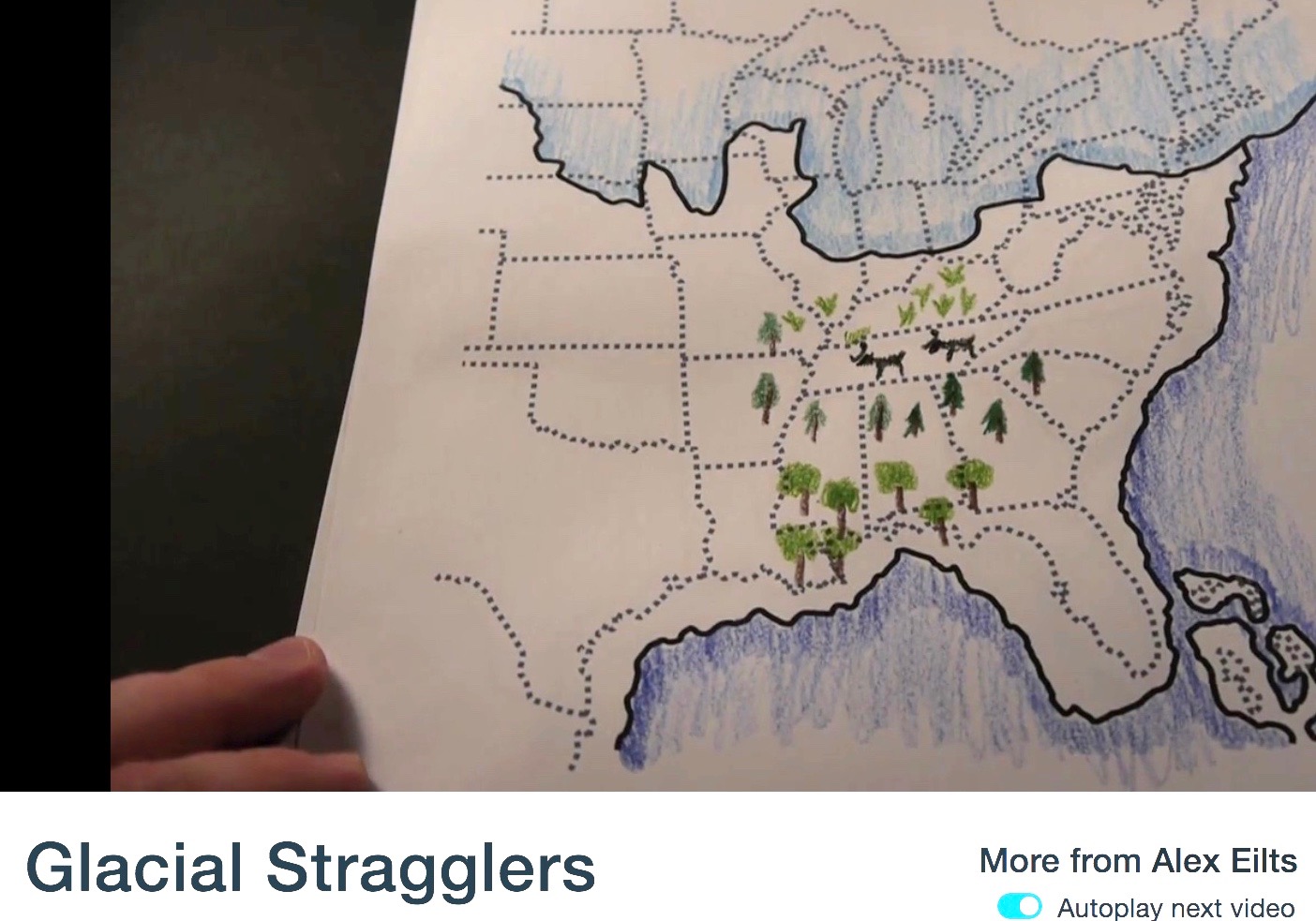

VIDEO: "Glacial Stragglers": Here the Apalachicola is presented as a peak glacial refuge.

FLORIDA ANISE is featured as a species that didn't get very far north post-glacial (timecode 12:48).

FLORIDA YEW (13:50) and FLORIDA TORREYA (14:25) are featured as species that were entirely left behind. (Scientifically, "glacial relicts".)

Quote by Alex Eilts: "Ironically, they are now trapped in the same place that sheltered them in the past. But now as the the climate warms, their refuge — turned prison — may lead to their extinction."

|

Note: Mark Gelbart hypothesizes that Mastodons, rather than tortoises (or squirrels) were the dispersers of Torreya taxifolia during the Pleistocene. See also his blog contending that Torreya is missing its megafaunal disperser. In the latter blogpost, Gelbart draws from a 1978 book by Charles Wharton, The Natural Environments of Georgia, in which the Torreya's very limited habitat in Florida is described as "torreya ravines." Associated plants are listed:

"The dominant trees in a torreya ravine are red maple, southern sugar maple, beech, magnolia, basswood, elm, torreya, and sabal palm. Most of these species have northern affinities and are more commonly found in Appalachian cove forests. Other plants found in torreya ravines also represent species of northern affinities such as strawberry bush, hydrangea, and redbud. Wharton found torreya growing with beech, sourwood, and plum in the Faceville Ravine on the Flint River."

ASSOCIATED SPECIES: "Florida torreya is not included among the forest cover types established by the Society of American Foresters but is

commonly known to be among the oak-gum-cypress or oak-pine

types. In 1919, it made up about 4 percent of the forest along the

Apalachicola River. The most commonly associated species are

beech (Fagus grandifolia), yellow-poplar (Liriodendron

tulipifera), American holly (Ilex opaca), Florida maple (Acer

barbatum), loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), spruce pine (P. glabra),

white oak (Quercus alba), eastern hophornbeam (Ostrya

virginiana), and sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua). Shrubs and

lianas associated with Florida torreya are poison-ivy

(Toxicodendron radicans), greenbriar (Smilax spp.), crossvine

(Bignonia capreolata), yaupon (Ilex vomitoria), Florida yew

(Taxus floridana), blackberry and dewberry (Rubus spp.). Forbs,

grasses, and sedges include sedges (Carex spp.), panic grass

(Panicum spp.), partridgeberry (Mitchella repens), little sweet

Betsy (Trillium cuneatum), giant cane (Arundinaria gigantea),

and American climbing fern (Lygodium palmatum)." — Silvics Manual, Volume 1: Conifers (Click on Florida Torreya).

• VIDEO: Site Visits to Florida's Endangered Torreya and Yew Trees

|

|

Connie Barlow presents 15 years of baseline photos and videos she recorded of Torreya taxifolia and Taxus floridana in their historically native range in Torreya State Park in northern Florida. Photos of spectacular California Torreya trees, recorded by Barlow in 2005, show the potential for Florida Torreya recovery efforts to strive for. Fred Bess shows (in 2014 video) 2 Asian conifers (Cephalotaxus and Cunninghamia) used in landscaping that are Torreya look-alikes. Paleoecological evidence that Florida's Torreya was "left behind" in its peak glacial refuge supports "assisted migration" actions. 63 minutes - assembled & published, January 2016 |

• Learn why T. tax is at the brink of EXTINCTION.

Classic Writings on Florida Torreya

In the spring of 1875, distinguished Harvard botanist Asa Gray embarked upon a trip to the panhandle of Florida, to "make a pious pilgrimage to the secluded native haunts of that rarest of trees, the Torreya taxifolia". The trees observed by Gray grew up to a meter in circumference and were as much as 20 meters tall.

|

"... One young tree, brought or sent by Mr. Croom himself, has been kept alive at New York [Central Park] — showing its aptitude for a colder climate than that of which it is a native — and has been more or less multiplied by cuttings..."

|

EXCERPTS FROM "A PIOUS PILGRIMAGE":

"... The people of the district knew it by the name of 'Stinking Cedar' or 'Savine' — the unsavory adjective referring to a peculiar unpleasant smell which the wounded bark exhales. The timber is valued for fence-posts and the like, and is said to be as durable as red cedar. I may add that, in consequence of the stir we made about it, the people are learning to call it Torreya. They are proud of having a tree which, as they have rightly been told, grows nowhere else in the world...

"The largest [Torreya] tree I saw grew near the bottom of a deep ravine; its trunk just above the base measured almost four feet in circumference, and was proportionally tall. But it was dominated by the noblest Magnolia grandiflora I ever set eyes on, with trunk seven and a half feet in girth.... Seedlings and young trees are not uncommon, and some old stumps were sprouting from the base, in the manner of the California Redwood...."

"One young tree, brought or sent by Mr. Croom himself, has been kept alive at New York — showing its aptitude for a colder climate than that of which it is natve — and has been more or less multiplied by cuttings."

[Referring to] "the central and upper portions of Alabama and Georgia, where Torreya is unknown, but I fancy it may once have flourished. I cannot here detail the reasons for this supposition."

"Seedlings and young trees are not uncommon, and some old stumps were sprouting from the base, in the manner of Californian Redwood. So this species may be expected to endure, unless these bluffs should be wantonly deforested — against which their distance from the river and the steepness of the ground offer some protection. But any species of very restricted range may be said to hold its existence by a precarious tenure."

"Returning to the boat at nightfall, I brought with me thirty or forty seedling Torryas, which, being too far advanced to be safely sent far north this spring, have been successfully consigned to the excellent Mr. Berckman's care, at Augusta, Georgia. I hope that one or more of them may in due time be planted upon the grave of Torrey."

Editor's note: Dr. John Torrey, 1796-1873, is buried at Long Hill Cemetery, Stirling, Morris County, NJ Plot = SW corner (Presbyterian section) Memorial ID 8306740

A.W. Chapman's Torreya Experience, 1885

LEFT: Map published in 1885 of Torreya's native range, in report by A.W. Chapman

RIGHT: Map of 20th century range of Torreya taxifolia, from "Defining Indigenous Species: An Introduction" by Mark W. Schwartz, chapter in Assessment and Management of Plant Invasions, 1997.

Online access to Chapman's report in the April 1885 Botanical Gazette:

Torreya taxifolia "occupies a narrow strip of land extending along the east bank of the Apalachicola River from Chattahooche on the north to Alum Bluff on the south, a distance of about twenty miles, and forming a continuous forest, but in detached and often widely separated clumps or groves, generally mingled with, or overshadowed by, magnolia, oaks, and other native trees. . . It is a wild, hilly region, abounding in rocky cliffs and deep sandy ravines ("spring-heads") and unlike in scenery and vegetation any other part of the low country known to me. To these cliffs, and to the precipitous sides of the ravines, the tree appears to be exclusively confined; for it is never seen in the low ground along the river, nor on the elevated plateau east of it, nor, indeed, on level ground anywhere. Hence, although the suggestion may appear a startling one, were the trees of the whole region growing side by side in one body, I estimate that an area of a few hundred acres would suffice to contain all of them.

... But its chief value is due to the remarkable durability of its

wood when exposed to the vicissitudes of climate; for it is credibly reported that some fences constructed of it sixty years ago still remain in sound condition. In consequence of this peculiarity it is now extensively employed by the inhabitants of the surrounding country for posts, shingles, and other exposed constructions. In view of these facts, the future of our Torreya is a matter calculated to excite very grave apprehensions. A tree possessed of such valuable qualities, occupying an area so limited

in extent, and in the midst of a population where the old rule of "Let him take who has the power, And let him keep who can" has unlimited sway, is destined, it is to be feared, to ultimate extinction.

Let us indulge the hope that the interest which is beginning to be manifested in regard to the preservation of our forests generally, may result in measures statutory or otherwise for its preservation.

1890 Editorial Reports Common Name Switch to Torrey-Tree

MAY 7, 1890 issue of Garden and Forest, page 222 excerpt:

"...Trees, which are usually of importance to man or sufficiently conspicuous to attract his attention, obtain naturally local vernacular names before science imposes others on them, and the common names once engrafted on a language, almost always hold their own among the people of the country where the trees are found. It was a matter, therefore, of much interest and some surprise to hear recently, in western Florida, the Torreya taxifolia, one of the rarest of all our trees, spoken of generally as the 'Torrey-tree'; and to find that Stinking Cedar, the unattractive name by which this tree was first known to the inhabitants of western Florida, was gradually being replaced by that of one of the Nestors of American botany.

The reason for this change is found perhaps in the fact that this tree, from its rarity, the interest attached to the geographical distribution of the small genus to which it belongs, and the reverence which his successors have always felt for the name of John Torrey, has several times been visited in its remote and isolated stations on the banks of the Appalachicola by men of science from distant parts of the country. When the people of the region, therefore, found that men of mature years and apparently in the enjoyment of all their faculties had journeyed thousands of miles merely to look at a tree which they had always considered as valuable only because it furnished indestructible material for fence posts, their own interest and curiosity became aroused; and therefore hearing these eccentric strangers talking always about Torrey and Torreya, the name has gradually become fixed, and now 'Torrey-tree' may often be heard in at least two or three counties of west Florida."

Three articles (1905, 1905, 1945) present Florida Torreya as

a northern-adapted tree displaced southward by the continental glacier